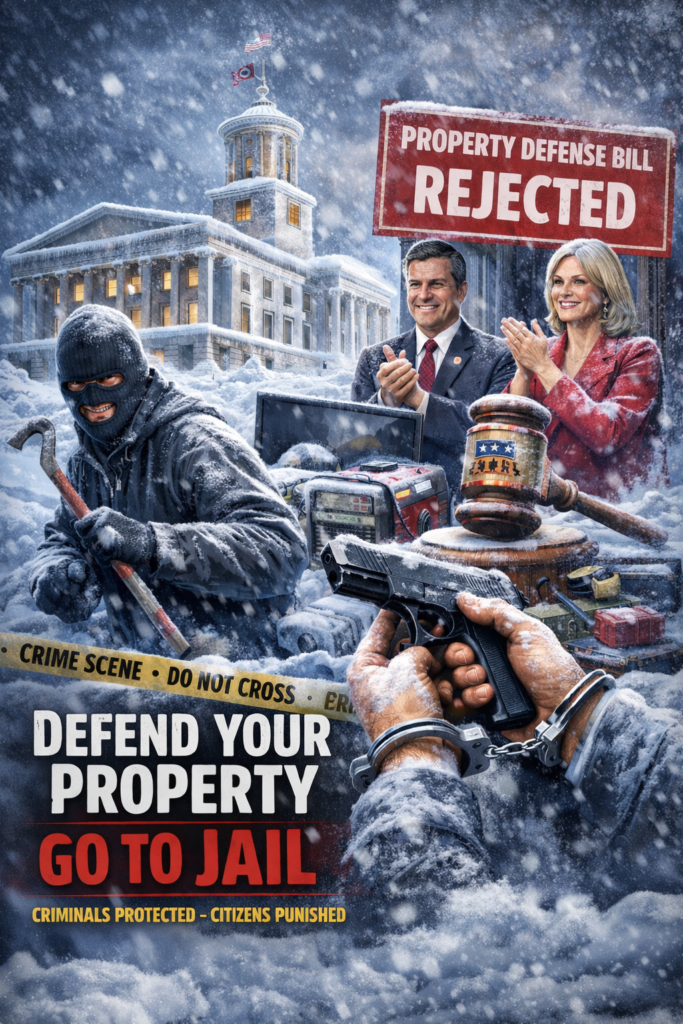

As Tennessee prepares for a severe winter storm system arriving this weekend, January 23–25, 2026, the Tennessee Firearms Association urges all Tennesseans—especially our members—to stay informed, prepared, and aware of the serious legal restrictions that still govern the defense of your home, business, and property.

The National Weather Service is forecasting heavy snowfall of a few inches to more than a foot in higher elevations, ice accumulations of up to an inch across parts of the state, freezing rain, strong winds, and dangerously low wind chills. These conditions are expected to cause road hazards, widespread power outages, downed trees and power lines, and potential disruptions lasting several days or perhaps weeks in some instances. Emergency management officials are advising residents to stock emergency supplies, secure generators safely, and prepare for extended periods without electricity.

Natural disasters unfortunately create opportunities for opportunistic crime. This obviously occurred in East Tennessee following Hurricane Helene in September 2024, when flooding left communities vulnerable and looting became a real concern. TFA addressed this issue directly in our October 2024 article:Tennessee Law Prohibits Property Owners from Protecting Themselves Against Looters and tried to address the issue again in the Legislature in 2025.

With similar risks now looming—thieves targeting generators, fuel cans, food, or unsecured homes during prolonged blackouts—it is essential that every Tennessean understands the current state of Tennessee law.

Tennessee Law on Use of Deadly Force to Protect Property

Under Tennessee Code Annotated §§ 39-11-614 and 39-11-615, it is a serious criminal offense to use “deadly force” for the sole purpose of protecting real property or personal property (yours or another’s). These statutes allow the use or threat of non-deadly force to prevent or terminate criminal trespass or interference with property. However, they expressly prohibit the use or threatened use of deadly force unless the situation independently qualifies under other self-defense statutes (for example, an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury to a person).

Importantly, Tennessee law defines “deadly force” broadly. It includes not only actually causing physical injury or death, but also the mere brandishing, display, or pointing of a firearm or other deadly weapon in a manner intended or likely to cause fear of imminent death or serious bodily injury. Brandishing a firearm to deter a thief can therefore constitute deadly force—even if no shot is fired and no one is injured. The result: what may be charged as aggravated assault, which is a felony that can result in years in prison and the loss of civil rights, against the homeowner can be more severe than the criminal charge the thief might face for simple theft or burglary.

Example Scenario During This Storm

Power is out for days. Your generator is the only source of heat for an elderly family member or for life-sustaining medical equipment. A thief approaches your property to steal it. You step outside, display a firearm, and order the thief to leave. Under current Tennessee law, that act of brandishing can be prosecuted as a felony against you—potentially carrying a harsher penalty than the theft itself. This is not hypothetical. This is the law today. Worse, this is the choice that Tennessee’s Republican controlled Legislature has elected to preserve as the law.

The Castle Doctrine Does NOT Override the Property Defense Prohibition

Tennessee’s Castle Doctrine (§ 39-11-611) creates a presumption that a person who unlawfully and forcibly enters or attempts to enter your occupied home, occupied vehicle, or occupied place of business poses an imminent threat of death or serious bodily injury. In such circumstances, you may use deadly force without any duty to retreat if all of the statute’s conditions are satisfied.

However, the Castle Doctrine applies only when there is a reasonable belief of imminent danger to a person—not when the only concern is theft or damage to property. If an intruder is stealing valuables, breaking windows, or removing a generator but is not threatening anyone with bodily harm, the Castle Doctrine provides no legal protection for using or threatening deadly force to stop the property crime alone.

Stand Your Ground Expansion – The Reform Tennessee Needs

Tennessee’s current Stand Your Ground law (TCA § 39-11-611) removes any duty to retreat before using force in any place where you are lawfully present, provided you reasonably believe force is immediately necessary to protect against another’s unlawful use of force. Yet this protection is still limited to threats against persons—not property crimes standing alone.

For more than a decade, the Tennessee Firearms Association and its grassroots members have fought to expand Stand Your Ground principles to explicitly allow the use of force—including deadly force when reasonably necessary—to prevent or terminate:

- Burglary of an occupied dwelling

- Arson

- Theft, robbery, or looting

- Trespass that threatens substantial property loss

- Theft of or cruelty to livestock or working animals

Legislation has sought to close this dangerous gap. These bills would have restored to law-abiding citizens the legal authority to defend their homes, businesses, and property during emergencies without fear of becoming the prosecuted party. Yet, the Legislature has repeatedly chosen to reject these efforts.

Repeated Betrayal by Republican Leadership and the Majority of the Republican Caucus

Despite controlling both chambers of the General Assembly and the Governor’s office, Tennessee Republicans—led by Governor Bill Lee’s administration—have consistently refused to pass these common-sense reforms. They have blocked legislation year after year, choosing instead to preserve laws that disarm victims in their own homes and businesses while criminals operate with relative impunity.

TFA and its members have begged, petitioned, testified, and campaigned for change. The response has been silence, excuses, or outright opposition.These elected officials have shown us who they are. They have chosen to prioritize the “rights” of thieves, looters, and burglars over the constitutional rights of law-abiding Tennesseans to defend what is theirs—especially during times of crisis.

Your Safety – Practical Steps for This Weekend

- Prepare now: Stock food, water, medicine, batteries, flashlights, and fuel. Secure generators away from windows and doors.

- Use non-lethal deterrence: Motion-activated lights, audible alarms, visible security signs, and neighborhood watch coordination.

- Document everything: If you must confront a suspicious person, record video if safe to do so and call law enforcement immediately.

- Know your legal boundaries: Do NOT rely on brandishing a firearm as your first or only response to a property crime.

- Make sure your insurance is current.

These are prudent precautions—but they are not a substitute for real legal reform.

Call to Action – It Is Time for Real Change

Asking the current leadership to fix this problem has proven futile. They have had years. They have had majorities. They have had our support—and they have betrayed it.The only remaining path is to replace those who refuse to protect our rights.

- Join or renew your TFA membership today and support our ongoing legislative and legal efforts.

- Contact your state representative and senator immediately. Use this link to find and message them: https://wapp.capitol.tn.gov/Apps/fml2022/search.aspx

- In the next election cycle, support and vote for candidates who commit to no-compromise Second Amendment rights and genuine self-defense reform—regardless of party label.

- Donate to TFA to help fund our advocacy, legal defense funds, and grassroots campaigns.

TFA has been Tennessee’s only no-compromise gun rights organization for 30 years. We will not stop fighting until Tennesseans can defend their homes, families, and property without fear of becoming the criminal in the eyes of the law.

Stay safe. Stay vigilant.

And let’s make 2026 the year Tennessee finally honors the right to self-defense—without apology.