On June 23, 2022, the United States Supreme Court released its long awaited 6-3 decision in the New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc., et al. v. Bruwen, et al, No: 20-843. It is an extensive 135 page opinion of which the majority opinion by Justice Thomas is 63 pages. This opinion will generate more litigation for years to come but it does hold, reversing much of the case law since the Court’s decisions in Heller (2008) and McDonald (2010) that the Second Amendment protects the individual right of citizens to carry a handgun outside the home for self-defense purposes.

In the very first paragraph of his opinion for the majority, Justice Thomas cuts to the chase by stating:

In District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U. S. 570 (2008), and McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U. S. 742 (2010), we recognized that the Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect the right of an ordinary, law-abiding citizen to possess a handgun in the home for self-defense. In this case, petitioners and respondents agree that ordinary, law-abiding citizens have a similar right to carry handguns publicly for their self-defense. We too agree, and now hold, consistent with Heller and McDonald, that the Second and Fourteenth Amendments protect an individual’s right to carry a handgun for self-defense outside the home.

As further detailed in the Court’s opinion, the main issue in the case was a statutory structure in New York where citizens were required to have permits to carry a handgun in public. Under that statutory structure the burden was on the citizen to demonstrate “good cause” to justify the desire to have a permit. New York’s attorneys had argued in the oral arguments that such “good cause” laws were permissible because states like Tennessee had long histories, dating back to the early 1800s, of making it a crime for people to carry firearms in public. See, for example, current Tennessee Code Annotated § 39-17-1301(a)(1) and its predecessors.

The Court struck down the New York “good cause” standard with ease:

*** We therefore turn to whether the plain text of the Second Amendment protects Koch’s and Nash’s proposed course of conduct—carrying handguns publicly for self-defense.

We have little difficulty concluding that it does. Respondents do not dispute this. See Brief for Respondents 19. Nor could they. Nothing in the Second Amendment’s text draws a home/public distinction with respect to the right to keep and bear arms. As we explained in Heller, the “textual elements” of the Second Amendment’s operative clause— “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed”—”guarantee the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation.” 554 U. S., at 592. Heller further confirmed that the right to “bear arms” refers to the right to “wear, bear, or carry . . . upon the person or in the clothing or in a pocket, for the purpose . . . of being armed and ready for offensive or defensive action in a case of conflict with another person.” Id., at 584 (quoting Muscarello v. United States, 524 U. S. 125, 143 (1998) (Ginsburg, J., dissenting); internal quotation marks omitted).

This definition of “bear” naturally encompasses public carry. Most gun owners do not wear a holstered pistol at their hip in their bedroom or while sitting at the dinner table. Although individuals often “keep” firearms in their home, at the ready for self-defense, most do not “bear” (i.e. carry) them in the home beyond moments of actual confrontation. To confine the right to “bear” arms to the home would nullify half of the Second Amendment’s operative protections.

Moreover, confining the right to “bear” arms to the home would make little sense given that self-defense is “the central component of the [Second Amendment] right itself.” Heller, 554 U. S., at 599; see also McDonald, 561 U. S., at 767. After all, the Second Amendment guarantees an “individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation,” Heller, 554 U. S., at 592, and confrontation can surely take place outside the home.

Although we remarked in Heller that the need for armed self-defense is perhaps “most acute” in the home, id., at 628, we did not suggest that the need was insignificant elsewhere. Many Americans hazard greater danger outside the home than in it. See Moore v. Madigan, 702 F. 3d 933, 937 (CA7 2012) (“[A] Chicagoan is a good deal more likely to be attacked on a sidewalk in a rough neighborhood than in his apartment on the 35th floor of the Park Tower”). The text of the Second Amendment reflects that reality.

The Second Amendment’s plain text thus presumptively guarantees petitioners Koch and Nash a right to “bear” arms in public for self-defense.

The Court’s opinion also noted, and rejected, the “two-part” analysis that many federal courts had adopted since Heller and McDonald to continue to validate state and federal restrictions on the rights of citizens as protected by the Second Amendment. In outright rejecting that popular “two-part” deferential analysis that had evolved, the Justice Thomas wrote:

Despite the popularity of this two-step approach, it is one step too many. Step one of the predominant framework is broadly consistent with Heller, which demands a test rooted in the Second Amendment’s text, as informed by history.But Heller and McDonald do not support applying means-end scrutiny in the Second Amendment context. Instead, the government must affirmatively prove that its firearms regulation is part of the historical tradition that delimits the outer bounds of the right to keep and bear arms.

* * *

In sum, the Courts of Appeals’ second step is inconsistent with Heller’s historical approach and its rejection of means-end scrutiny. We reiterate that the standard for applying the Second Amendment is as follows: When the Second Amendment’s plain text covers an individual’s conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s “unqualified command.” Konigsberg, 366 U. S., at 50, n. 10.

Indeed, Justice Thomas quite clearly rejected the deference which the federal court’s had shown toward legislative deference by noting that the Second Amendment’s very existence negated the tendency of any court to defer to legislative discretion, or indiscretion, in regulating the rights protected by the Second Amendment:

If the last decade of Second Amendment litigation has taught this Court anything, it is that federal courts tasked with making such difficult empirical judgments regarding firearm regulations under the banner of “intermediate scrutiny” often defer to the determinations of legislatures. But while that judicial deference to legislative interest balancing is understandable—and, elsewhere, appropriate—it is not deference that the Constitution demands here. The Second Amendment “is the very product of an interest balancing by the people” and it “surely elevates above all other interests the right of law-abiding, responsible citizens to use arms” for self-defense. Heller, 554 U. S., at 635. It is this balance—struck by the traditions of the American people—that demands our unqualified deference.

But Tennessee is not New York. So does this opinion mean anything for Tennesseans?

Most certainly it does!

First, it will likely impact how the Supreme Court approaches other cases that are pending in the federal court and how lower federal courts will deal with pending and to be filed cases.

Second, it will impact laws in states like New York where Tennesseans may travel or vacation and will do so in ways not yet demonstrated.

But third, it may impact Tennessee law and do so in significant ways.

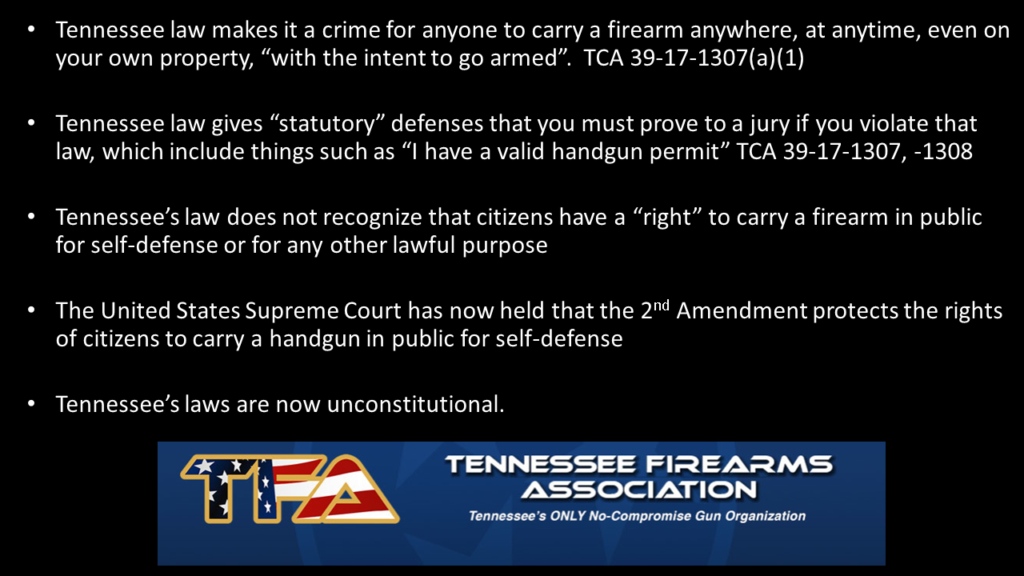

For example, Tennessee’s current law makes it a crime for anyone to carry a firearm in public with the intent to go armed. See, Tennessee Code Annotated § 39-17-1301(a)(1). This statute, as written, is simply incompatible with a constitutionally protected right. Sure, Tennessee has 4 confusing and potentially conflicting “defenses” to carrying a firearm with intent to go armed, which include 2 separate permitting systems, a poorly written permitless carry law and a fourth means for vehicle transport – but in each of these instances the citizen bears the burden of proving to an officer, a judge and/or a jury that they met all of the conditions required by the statutory defense. While the Court notes in a footnote that it is not addressing the “shall issue” permitting laws in the states, it does not that they are not presumptively constitutional particularly “where, for example, lengthy wait times in processing license applications or exorbitant fees deny ordinary citizens their right to public carry.”

In its historical analysis of laws that regulate or restrict the wearing of arms, the Court noted several different Tennessee laws and none of those were referenced favorably. The Court did indicate some understanding that state laws which prohibited threatening public use were common, and that laws which restricted concealed carry were not uncommon but it failed to speak favorably of any law – like Tennessee’s – which made it a crime for any citizen to carry a firearm in public unless certain conditions were met or which had the appearance of giving the citizen only a statutory defense to the criminal charge which could be raised only after being stopped, arrested and potentially charged with a crime. The Court did reference that Tennessee perhaps barely satisfied the constitutional standard when it had a law (that no longer exists) that said that a citizen could carry a handgun in public but only if it was an army or navy style of handgun. Again, now, in Tennessee there is not such “right”. The public carry of a firearm is a crime in all instances but there are a wide ranging and conflicting set of “statutory defenses” that one might raise if stopped, arrested or charged.

Then, Tennessee also has laws that create “gun free” zones in places like public parks, greenways, campgrounds, recreational areas, and public buildings. While the Court was not addressing gun free zones in this case, it did comment in dicta and did the Court in Heller that there are some possible restrictions or regulations on the constitutionally protected right which might survive constitutional challenge. As of now, those statements are collateral to the holdings and so the Court has not squarely decided or held that any such restriction is in fact a permissible infringement.

The Supreme Court has now held that it is a right for a citizen to carry a firearm in public. It is again long past time that Tennessee’s Legislature quit stonewalling and recognize that this is a fundamental human right, one of the few that are expressly protected by both the federal and state constitutions. The Tennessee Legislature can and must move forward as soon as possible to enact REAL constitutional carry – not just another statutory defense. It must also zealously review each and every statute that purports to restrict your right to carry in public and repeal most if not all of the gun free zone and similar restrictions that the Republican super majority has either enacted or protected in the last 12 years that they have totally controlled state government.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.